Unless you’ve been stranded on a desert island (we should all be so lucky), you will undoubtedly have heard the term “jobs and growth” bandied about the place as the federal election draws near.

Unless you’ve been stranded on a desert island (we should all be so lucky), you will undoubtedly have heard the term “jobs and growth” bandied about the place as the federal election draws near.

All sides of politics like to promise jobs and economic growth. People are generally reassured if they think that there will be jobs available for them and the economy is likely to grow.

But how realistic is this promise of job creation and economic growth?

Let’s look at jobs first. Governments don’t create jobs. Businesses do. And no, creating more government jobs is not job creation. At best, governments can foster an environment that is conducive for businesses to create jobs.

Let’s look at jobs first. Governments don’t create jobs. Businesses do. And no, creating more government jobs is not job creation. At best, governments can foster an environment that is conducive for businesses to create jobs.

Large infrastructure projects, even if they are public and private partnerships, are also not really job creators. These usually have a limited lifespan and do not create jobs for the long term. Once a project is finished, there are no ongoing jobs.

Compounding this is the fact that the whole jobs landscape is changing. Jobs are becoming more transient. Employers find they only need people for shorter periods and outsourcing has also changed the job environment. Businesses would rather put on casual or part time people than a full time person as it makes it easier to manage changing workloads. But this makes it harder for people looking for work and increases underemployment, something not being addressed by governments.

The nature of knowledge is also changing within the jobs framework. The amount of information in the world now is doubling every 18 months. To put that into perspective, 50 years ago, it took 25 years for information to double. It means that in some areas of knowledge, for a standard three year university degree there’s a distinct possibility that by the time the student graduates, what was taught and learnt in the first and possibly even the second year, is already obsolete. Many students will have degrees that are no longer useful by the time they graduate. There might not even be jobs in that industry. Our education system is not moving quickly enough to keep up with technological advances.

The nature of knowledge is also changing within the jobs framework. The amount of information in the world now is doubling every 18 months. To put that into perspective, 50 years ago, it took 25 years for information to double. It means that in some areas of knowledge, for a standard three year university degree there’s a distinct possibility that by the time the student graduates, what was taught and learnt in the first and possibly even the second year, is already obsolete. Many students will have degrees that are no longer useful by the time they graduate. There might not even be jobs in that industry. Our education system is not moving quickly enough to keep up with technological advances.

Experienced commentators and futurists are predicting that anywhere between 40 and 70 percent of jobs that exist today won’t exist in 10 years thanks to automation, artificial intelligence, robotics and virtual reality. It also means that there are new types of jobs being created now that didn’t exist a few years ago. Whoever heard of content marketers, social media engineers and virtual assistants until recently?

The focus needs to shift to entrepreneurism and innovation rather than the traditional job where a person works for someone else. People working for themselves, setting up micro or small businesses and solopreneurs are one of the few areas that is actually growing. Our education system needs to be more nimble and adaptable.

And then there’s economic growth. A growing economy is good for the country and the electorate, as this indicates economic stability, guaranteed jobs and other indicators like wage growth. However, realistically, governments can no more increase or create economic growth than they can create jobs, particularly in the current global economic climate.

And then there’s economic growth. A growing economy is good for the country and the electorate, as this indicates economic stability, guaranteed jobs and other indicators like wage growth. However, realistically, governments can no more increase or create economic growth than they can create jobs, particularly in the current global economic climate.

Let us look at some reasons why this is the case.

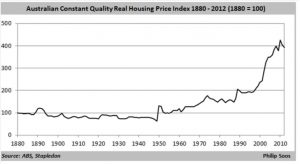

Firstly, we are in a global slow growth environment. Most developed countries are experiencing their slowest growth in decades. We are entering a deflationary period where asset prices are falling. I believe we are reverting back to the mean, as discussed in this previous post.

Most countries have tried various stimulatory measures. Central bankers use monetary policy by altering interest rates. In the past few years, most have reduced official interest rates to record low levels. In some countries, such as those in Europe, the interest rate is effectively zero and in others, such as Japan, Switzerland and Sweden, they have negative interest rates. This has not worked in stimulating their economies.

Low interest rates are supposed encourage people and businesses to borrow more thereby increasing demand. But that will only work up to a point. Interest rates are now so low, that any person or company that has wanted to borrow has done so by now. Instead, many people are taking advantage of the low rates to reduce their debt levels.

Low interest rates are supposed encourage people and businesses to borrow more thereby increasing demand. But that will only work up to a point. Interest rates are now so low, that any person or company that has wanted to borrow has done so by now. Instead, many people are taking advantage of the low rates to reduce their debt levels.

Reducing interest rates has its biggest effect early in the cycle of rate reductions. Thanks to diminishing marginal returns, each subsequent rate cut has a lesser and shorter impact than those made earlier in the cycle. Eventually they have no impact at all. I believe we are already at this stage and this is particularly evident in countries with zero and negative interest rates.

People and businesses cannot be forced to borrow more, particularly when they are already up to their eyeballs in debt. Australia has one of the fastest growing debt levels and our borrowing is at record levels already.

Governments are also increasing public debt levels, and in many countries, a great deal of this debt is to meet welfare requirements. Hardly a productive use of money. This also affects a country’s credit rating and makes credit more expensive if and when they are downgraded.

In addition, low interest rates have the effect of reducing confidence in the economy. Interest rates are usually only dropped in difficult economic times, so continually dropping them sends the message to people and businesses that the economy is not well and there are bad times ahead. Subsequently buying and investing slows or stops altogether.

Also with every interest rate cut, people who rely on interest for income such as savers and self-funded retirees, earn less and so spend less in the economy as their income drops. It also makes it harder for those who are saving for things like house deposits who earn less on their savings, thus delaying their entry into the market.

Demand for things is also falling. Manufacturers and countries relying on export, such as China and Japan, are finding that there is less demand for their goods. This is partly because the weaker economy erodes confidence in the market, and people are concerned for their jobs. They therefore decide they don’t need as many “things” or “stuff”. Many countries, such as China, have invested massive (borrowed) amounts on increasing the capacity of their factories and manufacturing just as demand slowed. Many of these plants are now underutilised or sitting idle.

Governments also don’t like deflationary periods. It reflects badly on them and their policies if the economy does not grow under their stewardship. In order to try and stimulate their economies, governments will use fiscal policies, or government spending. This gives the illusion of growth through increasing GDP figures, but this is at best a short term solution and rarely leads to long term growth and employment. Running stimulus or quantitative easing programs, more commonly known as money printing, presumes the money created will make its way to the greater economy by trickling through the banks to people and businesses.

Governments also don’t like deflationary periods. It reflects badly on them and their policies if the economy does not grow under their stewardship. In order to try and stimulate their economies, governments will use fiscal policies, or government spending. This gives the illusion of growth through increasing GDP figures, but this is at best a short term solution and rarely leads to long term growth and employment. Running stimulus or quantitative easing programs, more commonly known as money printing, presumes the money created will make its way to the greater economy by trickling through the banks to people and businesses.

The trouble with these programs is that very little of the printed money has actually made its way into the real economy. Instead, most of it has stayed with the banks or gone to large companies where they have used the funds to buy back their own shares. This increases stock market prices, but has not made a direct contribution into the economy.

Asset prices, such as real estate and stocks have been artificially boosted by people and investment funds searching for any yields they can find because they get nothing from holding cash. Unfortunately these asset price rises have nothing to do with productivity increases.

As previously mentioned, this stimulation is increasingly done with borrowed money, as few countries now run surpluses. Public and private debt burdens keep increasing. Unfortunately, private debt is increasingly funnelled into unproductive endeavours and assets.

As previously mentioned, this stimulation is increasingly done with borrowed money, as few countries now run surpluses. Public and private debt burdens keep increasing. Unfortunately, private debt is increasingly funnelled into unproductive endeavours and assets.

It doesn’t actually create jobs and has exponentially decreasing returns. In other words, it’s costing more money or debt, to create increasingly smaller returns. Where once every dollar invested might create greater returns than that initial dollar, now that invested dollar is returning less than the initial investment. These days the original dollar is debt, so we’re using more and more debt to create a lesser return.

This will ultimately create a drag on the economy and slow it down. We are already seeing the result of this with low growth, stagnating wages and low inflation and even deflation, because the economy is weighed down by this enormous unproductive debt hanging over it.

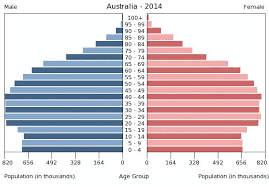

But the biggest reason for the low growth and slowdown in jobs is demographic change in developed countries. Almost all developed countries have smaller generations following the baby boomers. This means that the welfare and handouts that everyone has come expect as an entitled right may not be able to be funded, as the burden of paying for this falls on the next generation.

But the biggest reason for the low growth and slowdown in jobs is demographic change in developed countries. Almost all developed countries have smaller generations following the baby boomers. This means that the welfare and handouts that everyone has come expect as an entitled right may not be able to be funded, as the burden of paying for this falls on the next generation.

The Australian birth rate is below replacement at 1.8 children per couple. Our current immigration levels are enough to increase the population at this stage, but is this a sustainable model? It could be argued that the continent of Australia is not able to sustain the Big Australia vision of most of our politicians, given the vast interior of desert not suitable for agriculture and we are the second driest continent on the planet. Food and water security cannot be guaranteed.

Unfortunately our current and growing welfare requirements, demanded as a right rather than a privilege, depends on succeeding generations being larger than the preceding ones. Everybody wants the “free” education, “free” healthcare, disability allowances, faster broadband, greater pensions, stadiums and everything else expected to be provided by bigger and multiple levels of government. The trouble is nobody actually wants to pay for it. We all want someone else to pay. Obviously this is unsustainable, and was only ever really possible during the baby boom years.

So the bottom line is, in our current slowing productivity, slowing population and slowing credit environment, more jobs and economic growth are unlikely to happen without some forward and long term thinking by both politicians and the populace and real action taken now.